From Dallas to Frisco: A Change in Direction - Fulfilling Our Mission

When the Museum of the American Railroad embarked on its strategic planning process in the summer of 2006, one thing became very clear at the onset – we were out of space. In fact, that was the driving force behind the strategic planning effort. Secondly, our collection was way overdue to be covered by a permanent structure to provide protection from the elements. There were several other basic needs to be addressed in the planning process such as our desire to keep the present collection intact and to build a new facility that would be flexible and allow for the activities associated with a modern museum, particularly increasingly popular after-hours programs.

The Board of Trustees and staff entered into the process with an open mind and a willingness to do what was right for the museum as an institution and for the collection as its principal holding. The trend today is for museums to not engage in collecting at all, but to be venues for large traveling exhibitions. Our situation is quite the opposite, with our first acquisition dating back to 1963. What became the “Age of Steam” exhibit during that year’s State Fair of Texas would evolve into the 40-piece rolling stock, three landmark structure museum we have today. Amazingly, we have educated and entertained an estimated 3 million visitors on the same footprint for 45 years.

We knew we had reached the point of diminishing returns several years ago – probably about 1998. In looking back, it is apparent that our precious resources simply could not have provided us with the programming and presentation of the collection that we had envisioned at the time – no matter how hard we tried.

Back to the Strategic Plan…In working with Marcy Goodwin of Goodwin Associates, we tackled the issue of location and space about day-three of the process. We were hopeful that we could fit every other aspect of the plan into the Fair Park venue. However, we had also decided not to make the Strategic Plan site-specific, as it would have limited the outcome of the process. In the end, we created a plan that envisioned an exciting, new railroad museum that would require 9-15 acres at a minimum. During the planning process, we had extensive discussions about venues – including several outside the Dallas area – however, our hope was to remain a Fair Park institution.

The presentation of the finished Strategic Plan by Goodwin & Associates in the fall of 2006 was well attended by a number of stakeholders. They were genuinely impressed by the scope of work and the recommendations that came out of the planning process. That November 2006 would see the museum included in the Fair Park package of the bond program for Dallas. It was approved by the voters as part of a city-wide infrastructure improvements effort. Our share ($2.75 million), was to be matched dollar-for-dollar by the museum to acquire 1.4 acres across from the present site. This was in addition to an adjacent 1.9 acres that was to be provided in return for moving off the present footprint. This total of 3.3 acres was still far short of the 9 acre minimum. Over the next several months it became apparent that significant expansion beyond the 3.3 acres was going to be a very costly process that far exceeded the time frame in our Strategic Plan. Further, the museum would have to downsize its present operations in order to “fit” onto a portion of the new site for an indefinite period of time. It was also apparent that temporary track would have to be laid and then re-aligned at a later date after expansion onto the additional parcel.

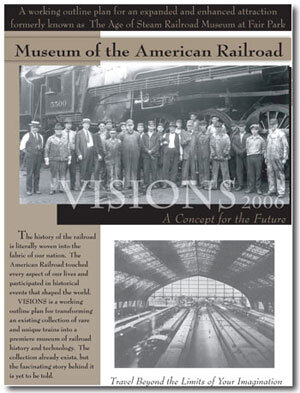

The museum’s 18 page Visions 2006 document was an important bridge between the concept of a larger, more significant museum and the formal Strategic Plan prepared by Los Angeles-based M. Goodwin Associates later that year.

The year 2007 would dawn with the promise of bond funds for the museum, but there were several attendant challenges associated with the project. These were equity funds requiring a 50/50 match, and some of the museum’s stakeholders had given us valuable feedback regarding investing in our present location.

Enter Frisco. The City of Frisco was experiencing phenomenal growth and was looking for opportunities to add new attractions and still preserve its small town heritage. They had just completed a re-branding of the city and adopted a new logo in the form of the Frisco Railway’s original raccoon skin design. There was interest among several on Frisco’s city council and in the City Manager’s office to expand on the railroad theme and tie it to the heritage effort. The city became aware of our online Visions 2006 document, and learned of our expansion plans. Excited about Visions, Frisco contacted us in early 2007. We agreed to meet with city officials and discuss our needs and the city’s plans for future cultural projects. They shared their exciting plans with us including their desire to bring a major railroad-themed attraction to the city. It became apparent very quickly that they were serious and had the wherewithal to execute such a project.

Discussions between our museum and Frisco continued for several months, with each meeting revealing the mutual benefits of relocating our collection to this vibrant North Texas community. We met several times in Frisco, and observed firsthand the unprecedented growth in this area and the opportunities that lie ahead. More importantly, we became very confident in the city’s ability to manage this growth and complete major civic projects. At the same time, events in Dallas further dictated serious consideration of Frisco’s overture.

The City of Frisco had consulted with us during the acquisition and restoration of the steam locomotive (ex- Grand Canyon Railway 19, nee Lake Superior & Ishpeming) currently on display adjacent to their heritage village. During one of our visits, museum representatives toured the new Heritage Museum, then under construction. The museum, a two-storey brick structure reminiscent of downtown storefronts in early Frisco, is the centerpiece of the new Heritage Village. We were impressed with Frisco’s dedication to preserving its heritage and the amount of resources they were willing to allocate to the effort. The city shared our vision and saw our potential of becoming the premiere museum of history and technology in the Southwest. The basic tenets of an agreement were reached between Frisco and the museum late in 2007.

The Heritage Association of Frisco and the City of Frisco teamed up to acquire ex-Lake Superior & Ishpeming Locomotive #19 (ALCO, 1910). Now on display in Heritage Park, the locomotive was well received and inspired City officials to expand on the idea of an exhibit of vintage trains in celebration of Frisco’s railroad heritage.

Finally, on April 1, 2008 the railroad museum entered into a formal letter of agreement with the City of Frisco to relocate to that city. The agreement received unanimous approval by the Mayor and City Council that evening and news of the project appeared in the Dallas Morning News a few days later. There is great excitement among both parties as we move forward to create this exciting destination in North Texas.

What Goes, and When?

The most frequently asked questions pertain to how much of the collection will go to Frisco and when they will start moving. The short answer is that everything goes and the process will begin to take place in about a year. The museum rosters just over 2,600 feet of rolling stock when coupled together in one continuous train. There is no track at the site presently; however proximity to the BNSF Main Line makes rail access relatively easy. We are planning to lay approximately 4,000 feet of track at the new 12.34 acre site in Frisco as part of Phase I construction.

Santa Fe Tower 19 will once again take to the road as it did in this August 1996 photo during its move to Fair Park. This will be the most challenging structure to move due to its excessive height.

With 27 pieces currently in Fair Park and 9 stored off-site, the movement of the rolling stock collection will entail an enormous amount of preparation and diligence to relocate the 30 miles north. We anticipate moving these pieces in manageable amounts, i.e. the heavyweights in one train and the vintage diesels in another. The steam locomotives will obviously require the most attention. We are soliciting bids on transporting the structures, which include the circa 1900 H&TC Yard Office/Station, the speeder shed of the same origin, and the 1903 Santa Fe Interlocking Tower 19. They will most likely require some disassembly due to width and height restrictions. Tower 19 poses the greatest challenge due to its excess height. At nearly 26 feet without its concrete base, the tower will require much prior planning and expertise.

A Few Words About Dallas…

The Museum of the American Railroad, formerly the Age of Steam Railroad Museum, has been a Dallas institution for nearly 50 years. While we have originated programming from the same location in Fair Park since the inception, our collection has grown in size and national significance. We had reached the point of diminishing returns at our tiny footprint in Fair Park, and it was clear we were unable to pursue our new mission and vision.

We have enjoyed our relationship with the City of Dallas and other Fair Park campus family members for many years. It is with some sadness that we pursue our dream elsewhere. However, we are not leaving Dallas, we are moving to Frisco. In other words, we will continue to offer high quality programming to all of North Texas from a larger venue that allows for future growth.

Affectionately known as “The Holy Land”, the early Age of Steam exhibit was a Sundays only operation between Fairs.

In 1963, when the “Age of Steam” exhibit opened under the auspices of the State Fair of Texas, the collection consisted of the H&TC Depot, Union Terminal locomotive #7, and an ex NYC “Mohawk” locomotive masked as a T&P M-2 class engine. The collection had grown to 36 pieces of rolling stock by 2006, but our footprint remained essentially unchanged. Railroad museums by their very nature require an enormous amount of space, and when compared to other similar operations, we should be occupying at least nine acres. Real estate at Fair Park is at a premium, particularly during the State Fair. The City of Dallas was sympathetic to our needs and we are very grateful for having been included in the 2006 bond program to provide equity funds for the purchase of 1.4 acres, however, vast sums of money were needed to acquire additional property that, even in the aggregate, would not be sufficient to allow for adequate expansion of the museum.

If it weren't for the contributions and support of the City of Dallas and the State Fair of Texas, the Museum of the American Railroad would not have amassed and maintained such a fine collection of historic trains. We have benefited greatly from our association with so many fine organizations and individuals. Our inclusion in the City of Dallas Office of Cultural Affairs’ Cultural Operating Program was an important turning point in our operations. We have learned much from our association with OCA. We are also proud to be a part of the local arts advocacy groups including Big Thought and ArtsPartners.

Railroad museums have to try harder in general, particularly in an urban setting with so many other attractions. We are fortunate to have shared in the synergy of the other Fair Park arts & cultural institutions over the years. The success of the other museums became a mirror into which we looked for our own direction for growth.

A museum’s mission and vision are paramount and if they are to be realized, their governing bodies must assemble the resources necessary to be successful. The City of Frisco has realized the potential of our museum and is providing those resources. As we spend more time in Frisco, we've gained a better perspective on our present situation in Dallas - a museum with many aspirations, challenged by its present venue. We know that our decision to move is the right one. We look forward to moving the 30 miles north to Frisco, while fondly remembering our many years in Dallas. And, while we are physically moving our collections and operations, we are by no means leaving the Dallas market. We will continue to celebrate the rich history and heritage of railroads in Dallas, but from a location that allows us to grow and flourish.

The Look of the New Museum

Boston’s North Station of 1893 provides inspiration for the museum’s main station headhouse building. Designed by Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge of Boston, the building’s design elements will compliment Frisco’s surrounding streetscape when applied to the new museum’s entrance façade. North Station was razed in 1928 to make way for Boston Garden, however it is still considered architecturally significant among late 19th century structures.

The new museum will be built in phases, the first phase consisting primarily of the basic rail plant and facilities - over 1 mile of trackage to provide ingress/egress to the site and exhibition of the rolling stock collection. Phase II consists of permanent buildings that provide for the visitor center, exhibition halls, retail space, administrative offices, and special events facilities. Additionally, a massive train shed is to be constructed, providing shelter for the museum’s rolling stock collection and outdoor exhibits. The structure will be reminiscent of turn-of-the-century, open-truss train sheds found at major train stations throughout the U.S. and Europe. The museum’s preliminary site plan, approved by the City of Frisco in 2009, also includes a third phase of construction that provides for a locomotive roundhouse and turntable as part of a restoration/technology center.

The Visions 2006 document explores various museum building concepts. Principal among these concepts is the need to present the collection in an environment that is reminiscent of the era. The majority of our rolling stock collection consists of passenger cars and the locomotives that pulled them, making a large turn-of-the-century train station the ideal museum setting – more specifically a terminal station with several stub-end tracks.

The City of Frisco has created a downtown streetscape as part of a larger development project known as Frisco Square. While these buildings are all new construction, they exhibit architectural features from turn-of-the-century commercial structures.

Taking our station concept on pages 13 & 14 of Visions 2006 to the next level, we selected Boston’s Union Station of 1897 (later known as North Station) as the architectural inspiration for the new museum building. We first presented an image of this magnificent structure in the form of a hand- tinted post card view during our presentation to the Frisco City Council in April. It was enthusiastically received and has become an icon for the new museum and inspiration for other proposed buildings in Frisco’s new downtown. While an exact replication of North Station would not be economically feasible, the basic elements of this grand structure seem most appropriate for the new museum and its contents in Frisco.

In addition to providing indoor facilities to visitors year-round, the museum’s priceless collection of rolling stock will be covered, protecting it from the elements. This has been one of the highest priorities throughout the museum’s planning process. Landmark restrictions at Fair Park prevented the construction of a permanent structure to house the cars and locomotives that average 80 years in age. A train shed, providing nearly 100,000 square feet of cover, is a key element of the museum’s Phase II construction project in Frisco. It will be similar in construction and appearance to those used in to Boston, Chicago, St. Louis and other major cities at the height of rail travel. The train shed will abut the main building concourse, which serves as a transitional space between the two structures. The shed will incorporate the basic structural design elements as part of its architecture, i.e. open-truss supports. The structure will celebrate its method of support rather than conceal it – providing visual appeal that compliments the 1900-1930s era represented by key pieces in the rolling stock collection. The result will be a large interior space that is functional, yet offers great opportunities for a variety of museum activities and events.

Main concourse, St. Louis Union Station circa 1910

Train shed, B&O Grand Central Station, Chicago 1960s

In this 2008 view looking north across the 12.34 acres allocated to the new Railroad Museum, the rear of Frisco Municipal Center is visible at left. Luxury three-storey town homes are center to right and feature traditional architecture reminiscent of brownstone walkups. Just this side of the town homes and running left to right (west to east) is Cotton Gin Road which will front our museum. The urban streetscape of Frisco’s new downtown, known as Frisco Square, will be complimented by the museum’s proposed turn-of-the-century station headhouse / main building.

Frisco’s Heritage Museum Opens, Providing Interim Space for Railroad Museum Exhibits & Staff

Amid rapid growth and an unprecedented increase in population, Frisco city planners have set aside land and allocated resources to acknowledge the past. The $2.2 million Frisco Heritage Museum opened its doors on May 3, 2008 and is part of a planned Heritage Center complex that features historic homes and other structures from around Collin County. This rendering, looking north-northeast, shows the Center as it appears today. The site of the new Railroad Museum is approximately 1,000 feet to the south along the BNSF Railway at Cotton Gin Road.

On May 3, 2008 amid much anticipation and fanfare, Frisco’s new Heritage Museum held its grand opening. The two-story building features an exterior reminiscent of early downtown storefronts and houses interactive exhibits that tell the story of life in early Frisco. Included are interesting and informative displays on cotton production in Collin County, the early days of the Frisco Journal with a working print shop and, of course, the story of the Frisco Railroad and its dramatic effect on the burgeoning young town.

Also featured are items from the recently acquired Bolin Collection including antique Ford automobiles displayed as part of a vintage gas station exhibit. The Bolin Collection was acquired from the estate of this McKinney family that was a long-time distributor of Mobil petroleum products in Collin County.

With its prominent entrance rotunda resembling a water tank from steam era railroading, the Frisco Heritage Museum stands as a proud reminder of the City’s past. Model T Fords from the Bolin Collection bracket the entrance just prior to the ribbon cutting ceremony.

The Museum of the American Railroad has partnered with the Frisco Heritage Museum to develop an 850 square foot railroad display on the second floor. The exhibit features items from our collection that have never been displayed previously due to the lack of indoor space at Fair Park. Prominently displayed are the museum’s 1920s era handcar, a circa 1916 REA remains wagon from Dallas Union Terminal, and a functioning 1920s “wig-wag” crossing signal. Several pieces of dining car china are showcased in the exhibit pieces from the joint M-K-T – Frisco Texas Special. Bold wall graphics serve as a dramatic backdrop to the exhibit and feature images from SMU’s DeGolyer Library and the museum’s extensive photographic collection. The exhibit’s story-line covers the birth of Frisco as a result of the St. Louis-San Francisco Railway building through North Texas in 1902 and its relation to the national rail network.

The Heritage Museum has also graciously provided interim office space for us to establish a presence in Frisco and begin development and programming for the new railroad museum. In line with our Strategic Plan, we have satisfied an important interim step in building our new facility in that community. In return, we are providing the Heritage Museum with staff support, guidance toward AAM accreditation, and program development tailored to the needs of Frisco area schools and the tourism market.

The museum’s “wig-wag” crossing signal operates for visitors at the touch of a button. The Frisco EMD E-8 locomotive photo is reproduced to ¾ actual size in this dramatic wall graphic.

The Frisco Heritage Museum was originally envisioned by the Heritage Association of Frisco and in particular the late Dr. Erwin G. Pink, a long-time Frisco physician. The Museum is one of a handful of such institutions in cities with populations of 100,000 residents or less. On May 3rd, it opened its doors with the benefit of enthusiastic volunteers from the Heritage Association and the nearby Senior’s Center. Frisco natives and transplants from as far away as Germany greet visitors and help interpret exhibits and tell the story of life in early Frisco. The museum’s admissions and gift shop are staffed by persons from the nearby Frisco Public Library which is housed in the new George A. Purefoy Municipal Center. The City of Frisco has acknowledged its namesake railroad that had created a lake to satisfy the thirst of its steam locomotives. The lake spawned the town as the line built southward into Texas in 1902.

A Railroad... A Town... And A Bright Future...

The Railroad could literally make or break a town. When railroads were building through early Texas, there was intense competition to attract lines to communities – but it came at a price. Towns like Frisco would grow and prosper while other towns would be bypassed. Some were left to wither and die.

THE RAILROAD AS CHANGE AGENT…

The City of Frisco owes its name and its beginnings to the railroad. The new town was a result of a series of events dating back to the Civil War era. The nation had endured a long and bitter war that divided its people and all but halted its growth – including the progression of the railroad. Following the conflict, railroads were the growth industry much like technology is today. New areas were settled and great sums of money were made as railroads raced to build lines out ahead of an ever-expanding nation.

In 1862, Congress passed the Pacific Rail Act which mandated construction of the first Transcontinental Railroad. The Civil War caused great delay in the line’s funding and construction, but in 1869, just four years after the end of the war, our nation would finally be bound together by the new iron road. The speed and reliability of trains replaced the slow, unpredictable, and often deadly trek by horse & wagon.

Additional lines would quickly radiate from key points west of the Mississippi River including St. Louis and Kansas City. This set the stage for a period of unprecedented growth that would eventually reach north Texas and establish the city of Frisco.

The backers of this expansion, including opportunistic politicians, reaped the benefits of everything from steel production to land speculation to big profits from freight revenues. This new industry quickly fell under the control of a small number of powerful individuals. Known in their day as “robber barons”, they had a dramatic influence on commerce in the U.S. These men quickly formed other new railroad companies that set out to build additional routes to the Pacific in hopes of reaping the benefits a growing nation.

RAILS WEST – And Thence to Texas…

DeGolyer Library, SMU, Dallas

One such line was the St. Louis-San Francisco (Frisco) Railway. Chartered in 1876, the railroad assumed lines which had already begun construction westward and south from the Mississippi River’s edge in St. Louis. This was originally an effort by the Pacific Railroad, a line chartered by the Missouri Legislature in 1849. The Pacific Railroad was to link St. Louis with the state’s western border and connect with any line building from California.

Like many other ambitious rail projects of that era, the Frisco Railway would never reach its namesake city of San Francisco. However, following several line acquisitions including a branch to Springfield, Missouri, the St. Louis-San Francisco Railway would eventually connect vital areas in the nation’s middle region. The line reached Texas in 1901, setting the stage for growth in many existing and soon-to-be formed North Texas communities. The Frisco system would eventually reach the Gulf of Mexico in 1928, linking the Midwest with important water ports to the South. This created an important link between Texas cotton growers and mills along the eastern seaboard and abroad.

A NEW TOWN IS BORN…

The Frisco Railway had expanded southward through Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) to the Red River in an effort to tap into cattle movements in Texas. The line continued down through North Texas, extending from Denison to Carrollton in 1902. During construction, the railroad established a water stop a few miles northwest of Lebanon (an important point on the Preston Trail). That stop would help foster a community initially called Emerson – named after the original landowner & prominent resident in nearby McKinney.

The Black Land Town Site Company (a subsidiary of the Frisco Railway) was formed and began selling lots in the new community which already had a general store and lumber yard. A depot was soon constructed, with the first train arriving on March 20, 1902.

The new town of Emerson would begin life with the important advantage of being connected to the outside world by rail. The new railroad brought much needed materials and supplies, but most importantly, it provided a link for cattle raisers and local farmers to ship their product to distant markets. Renamed Frisco City and later Frisco, the town would officially be incorporated on March 3, 1908. Thomas Duncan, the town’s first Postmaster, is credited with the new name, having been impressed with the profound effect of the railroad on his community. Lebanon (the approximate location of today’s Stonebriar Mall), would not fare so well and would eventually succumb to being bypassed by the railroad.

DOWN AT THE DEPOT…

Like most towns, Frisco was assigned a local railroad manager. Known as a Station Agent, he sold tickets to passengers and prepared freight billing for shippers. Station Agents often became the face of the railroad and reflected the pulse of the community it served. He would also send and receive telegrams, the first form of instant communication. Depots were a portal to the world in small towns and telegraphy was the internet of its day. The new town of Frisco would soon revolve around its namesake’s depot. The townspeople would frequent the depot just to catch a glimpse of the outside world. For some 40 years, Harold Bacchus, a second generation railroader, served as the railroad’s agent in Frisco. He was well liked among residents, eventually becoming Mayor in 1966.

Frisco Depot circa 1955, Heritage Association of Frisco

A LINK TO THE WORLD…

By 1920, the peak year for rail mileage, the Frisco Railway had become a vital link in the nation’s 260,000 route mile network. The population of Frisco stood at 733 and the town was now originating countless bales of cotton and other agricultural products to be shipped by rail. Bound for points in the U.S. and abroad, Frisco and its citizens were having an effect on the rest of the world via the railroad. For decades, the railway and the town would see prosperous times and periods of difficulty. The Depression of 1929 caused great financial hardship on the railroads, but World War II would rebound the industry to record traffic levels. Frisco would help supply the war effort through materials and manpower.

DeGolyer Library, SMU, Dallas

Changes...

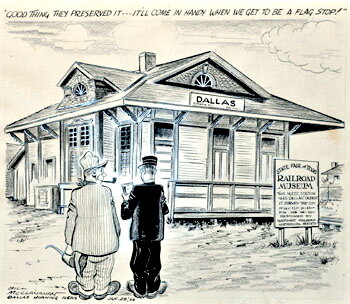

Following WWII, improved roads and commercial aviation would trigger an irreversible decline in the railroad industry. Trucks would offer flexibility and convenience for freight movements, while jets would lure passengers away from trains. The Frisco Railway would remain competitive in its freight operations, but its passenger service followed a national decline in travel by rail – a victim of the interstate highway. The town of Frisco had become a flag stop by the 1950s. Finally, on January 19, 1960 the last passenger train departed the town of Frisco, leaving its 1,184 citizens with no public transportation for the first time since 1902.

The depot, a gray board & batten wood structure with white trim, was demolished in 1965. It was the only passenger station erected in Frisco and was situated on the west side of the Frisco main line. The depot has been faithfully replicated as part of Frisco’s new Heritage Center and is available for special events.

In 1980, the railroad industry would be bolstered by a robust economy, de-regulation, and a climate more conducive to mergers. Later that year, the Frisco was merged into Burlington Northern, itself a conglomerate of several major western lines. This proved to be a wise decision which kept the original Frisco lines intact and viable. The merger created a 30,000 mile system serving 25 states - the longest single rail network in the US.

In 1995, Burlington Northern merged with the Santa Fe Railway, once the owner of the Frisco. Today, Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF) Railway continues to serve the city of Frisco through daily freight operations. While the majority of goods are now delivered by truck, trains, some exceeding a mile in length, still pass through Frisco each day. Pulled by massive locomotives exceeding 12,000 horsepower, some of these trains deliver aggregate rock to Frisco. This material satisfies the city’s thirst for more roads and other infrastructure as it experiences dramatic growth in the 21st century.

A BRIGHT FUTURE FOR RAILS…

Completed in June 2008, the City of Frisco faithfully reproduced its namesake depot. Located on the northeast corner of Frisco Heritage Center on Page Street, this new facility is situated just west of the BNSF (ex-Frisco main line) and is available to rent for special events.

In 2006, railroads moved more freight and produced more ton-miles than ever before in their history – including WWII. Deregulation, container traffic from overseas, and rising fuel prices have helped make the railroad industry viable and competitive in today’s transportation markets. Amtrak and new commuter rail lines like the Trinity Railway Express between Dallas and Fort Worth are decreasing our dependence on the automobile. With nearly 100,000 residents, Frisco may again see passenger rail service as light rail and commuter lines are constructed in North Texas to alleviate congestion and address environmental concerns. Frisco’s recent adoption of the St. Louis-San Francisco Railway’s raccoon skin logo is a tribute to the city’s rich railroad heritage and its commitment to the original promise of growth and prosperity brought about by the line.