The Pullman Porter

Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters

Service and Grace Amid a Class Struggle: The Story of the Pullman Porter

“The most influential black man in America for the hundred years following the Civil War was a figure no one knew. He was not the educator Booker T. Washington or the sociologist W.E.B. Dubois, although both were inspired by him. He was the one black man to appear in more movies than Harry Belafonte or Sidney Poitier. He discovered the North Pole alongside Admiral Peary and helped give birth to the blues. He launched the Montgomery bus boycott that sparked the civil rights movement – and tapped Martin Luther King, Jr. to lead both. The most influential black man in America was the Pullman Porter.” – Rising from the Rails: Pullman Porters and the Making of the Black Middle Class, Larry Tye, Holt & Company Press, 2004

To generations of travelers, the name Pullman was synonymous with impeccable service and style. Between 1870 and 1969, Pullman attached its sleeping cars to nearly every train that traveled over all or a portion of its route at night. At its peak in 1929, the company’s fleet of cars could sleep over 150,000 passengers each night. The system comprised 71 different contract railroads and over 115,000 miles of track nationwide. Pullman’s sleeping cars were staffed almost exclusively by African Americans. Known as Porters, they provided a level of service that far exceeds today’s standards of travel.

The Pullman Company was a separate business from the railroad lines. It owned and operated sleeping cars that were attached to most long-distance passenger trains. Pullman was essentially a chain of hotels on wheels. When passengers purchased a ticket to ride on a train, the railroad received the base fare. Travelers then had the option to upgrade from coach to a sleeping car accommodation. Passengers could purchase an upper or lower berth (bed) in a tourist-class sleeping car, or an individual private room in a first-class sleeper. The additional fare was charged by the Pullman Company and was usually thirty to seventy percent more than the basic coach ticket, depending upon accommodation. Pullman provided a Porter (attendant) that prepared the beds in the evening and made them in the morning. Porters attended to additional needs such as room service from the dining car, sending and receiving telegrams, shining shoes, and valet service. Pullman slept up to 38 passengers in tourist-class cars (also known as open-section sleepers). Porters often endured long hours, with passengers frequently boarding and de-training at station stops throughout the night. An accommodation might be vacated at 3:00am, only to be occupied again by a passenger boarding at the same station.

Pullman Porter, 1943. This image was captured in a series of photographs taken at Chicago Union Station by award winning FSA photographer Jack Delano.

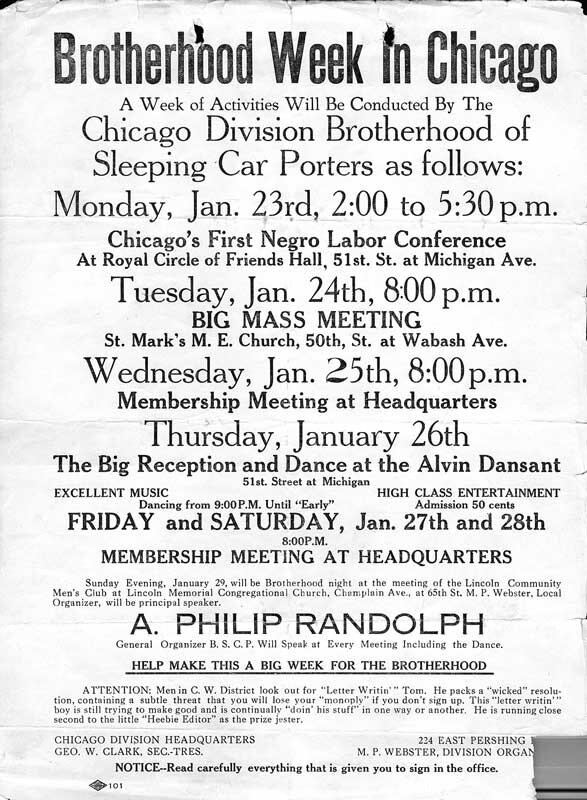

Porters were essentially at the beck and call of first-class passengers, however, they were otherwise invisible. The days were long, often affording less than three hours sleep in a 24 hour period. Working conditions were difficult even for the times. Porters began to meet in larger cities in an effort to address their needs and concerns. In August, 1925, at the opposition of the Pullman Company which staunchly opposed organized labor, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was formed. This organization, the first of its kind to represent African American workers, was supported by leaders in communities nationwide. In 1929, A. Philip Randolph, a New York social activist, was recruited from the outside to lead the newly formed organization and became its president. The union eventually entered into a collective bargaining agreement with Pullman, but more importantly, went on to be the foundation on which to advance civil rights issues. Initially organized in secrecy, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters grew throughout the years and eventually merged with the Brotherhood of Railway and Airline Clerks (BRAC).

Oakland, California’s First Pullman Porter’s Union. Oakland was a significant base of operations for Pullman and a domicile for Porters on the West Coast. In an effort to improve their working conditions, these Porters were among the first to organize. They played a key role in the development of The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in 1925, which successfully negotiated for fair wages and working conditions.

Photo Courtesy of the African American Museum and Library at Oakland (AAMLO)

While passengers were enjoying Pullman’s amenities en route to their destinations, a quiet class struggle was taking place aboard those sleeping cars. The almost exclusively African American ranks of Porters were absorbing the ways of the traveling elite – those who occupied first-class accommodations and whose worlds were more accessible aboard the train. While African Americans as passengers seldom saw the interiors of extra-fare sleeping cars, Porters witnessed white America in the most intimate of settings. These Porters would endure long hours and less than flattering comments from some passengers, all the while learning from their encounters and vowing to provide a better life for their children. Some Porters would gather magazines and newspapers left behind by passengers and distribute them throughout their communities along the routes. This provided many African Americans across the nation access to information not otherwise sought or available to them.

THE RISE AND FALL OF PULLMAN

Courtesy of Trains Magazine, Kalmbach Publishing

Known originally as “Palace Cars,” George Pullman’s sleepers became the standard bearer for comfort, service, and safety in the travel industry. Beginning in 1867 Pullman built and operated its own cars, contracting with the railroads for their use to provide overnight accommodations and club-car service. In 1929, Pullman’s peak year, the company sold nearly 34 million premium fares and faced little competition in the market. In 1940, the U.S. Government challenged Pullman in the courts, alleging it held a monopoly on the sleeping car business. The company was ordered to divest itself of sleeping car manufacturing operations as a result of an anti-trust judgment. By the 1950s, however, Pullman posed a threat to no one, with the irreversible decline of passenger train service already underway. The carrier survived the Great Depression and two World Wars, only to succumb to the Interstate Highway System and the jet. Pullman ceased operations in 1969, turning over its remaining sleeping car business to the railroad companies. In 1970, Congress passed the Rail Passenger Service Act (Railpax). This provided for the creation of the National Railroad Passenger Corporation, known as Amtrak. Today the traveling public can purchase sleeping accommodations on many intercity Amtrak routes. Several original Pullman cars survive at the Museum of the American Railroad - tangible artifacts from our rich industrial past and symbols of our cultural heritage.

THE JOURNEY CONTINUES

May 1, 1971, veteran Pullman Porters became employees of Amtrak

Amtrak Coach Attendant Harold Covington went to work for the Illinois Central Railroad in 1947 aboard the famed City of New Orleans. He retired from Amtrak in 1987 after 40 years of service.

The last wave of hiring Porters took place after the Second World War. The railroads were re-equipping their fleets of passenger trains with sleek, new streamlined equipment. These young Porters began their careers during a promising period of post-war travel by rail. Trains were being marketed as destinations unto themselves - getting there was half the fun. The Chicago-San Francisco California Zephyr was introduced in 1949 as America’s “vacation train”. Unfortunately, the Interstate Highway Act and the advent of jet aircraft triggered an irreversible decline in rail travel. The young Porters of the late 1940s presided over a slow death of the American passenger train by the 1960s.

In May, 1971, Amtrak assumed most of the Nation’s remaining passenger routes from the private railroad companies. The quasi-government corporation was established to save the passenger train and preserve a balanced transportation network in the U.S. While the advent of Amtrak offered great promise for the future of passenger rail, it signaled the end for many routes. Less than half of those trains operated prior to the takeover survived. Many Porters were eligible for retirement at the inception of Amtrak and took advantage of the route discontinuances. Others continued their careers as Amtrak employees aboard the new nationalized system of trains. The transition was not easy for some, as the culture had drastically changed. Amtrak had hired ex-airline executives to manage the fledgling carrier in hopes that their successes would carry over into rail travel.

“I started out on #58 and #59, that fast train on the IC between New Orleans and Chicago called the City of New Orleans. It carried everybody that couldn’t afford the first-class Panama Limited. I worked out there until Amtrak. Now I’m over here [on the Texas Eagle]. They call it the ‘Old Folks Train.’ All the Old Heads like me got seniority to work this train ‘cause its only one night out. I’m gonna retire soon and go back to Memphis. I’m gonna play dominoes with my friends and talk about my railroading days.” – Harold “Cowboy” Covington, 1984

The porters, many advanced in age, gracefully upheld a tradition of style and service while at Amtrak. The “Old Heads” as they were known by the 1980s, found themselves working beside younger Amtrak employees that had no prior experience on the rails. These graying Porters imparted the demeanor and high service standards of their predecessors to the newer Amtrak crewmembers. This left an indelible impression on the carrier and its younger, uninitiated employees. By the 1990s, nearly all of the original porters had retired, closing a period that dated back to the post Civil War era.

Representing a new generation of railroad workers, Velida Breakfield is a Locomotive Engineer for Amtrak’s Chicago-San Antonio Texas Eagle. A 22-year veteran with Amtrak, Ms. Breakfield poses at the controls of Amtrak’s 4,200 HP “Genesis” diesel locomotive in October, 2011.

Ted Henry worked aboard Santa Fe passenger trains as a dining car waiter in the 1960s. Known for impeccable food and service, Mr. Henry recounted his years with the Santa Fe during a museum oral history project in 2008. He retired before the advent of Amtrak.

Amtrak Sleeping Car Attendant Otho Moore began his career as a Pullman Porter in 1942 aboard the Pennsylvania Railroad’s first-class New York-Chicago Broadway Limited. He joined Amtrak in 1971, working 18 more years before retiring to his home in Indianapolis.

Travelers can still experience the romance and excitement of a private accommodation aboard a railway sleeping car. Amtrak offers these accommodations as an upgrade from coach-class on most of its overnight intercity passenger trains.

The term “Porter” has all but vanished in favor of “Attendant” - in fact, Porter has become somewhat of a derogatory term. What was traditionally an African American occupation is now filled by men and women of all ethnicities and backgrounds.

The Pullman Porters of yesterday left behind an important legacy of service and grace amid a class struggle to improve the lives of their children and grandchildren. Their accomplishments, including the advancement of civil rights and creation of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, paved the way for future generations of African American workers. Union leader A. Philip Randolph and several former Porters went on to influence public policy in Washington that ultimately led to passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

FOR MORE INFORMATION ABOUT PULLMAN PORTERS, WE SUGGEST:

AMS Pictures. Rising from the Rails: the Story of the Pullman Porter. DVD, 2007.

Pullman On-Board Staff, B&O Capitol Limited

Grand Central Station, Chicago

Retired Pullman Porter

Southern Railway